When Titan acquired a majority stake in online jewellery brand CaratLane Trading in 2016, India’s e-commerce story was faltering. Flipkart, the country’s largest online retailer, saw its gross merchandise value (GMV) stagnate, with investors subsequently slashing its valuation.

India’s consumer internet market was also in a state of disarray. Having failed to build out a business model, a slew of vertical-focused online retailers found themselves out of favour with investors. The likes of FabFurnish, Babyoye, and EkStop were subsequently acquired by large conglomerates such as the Future Group, the Mahindra Group, and Godrej, respectively.

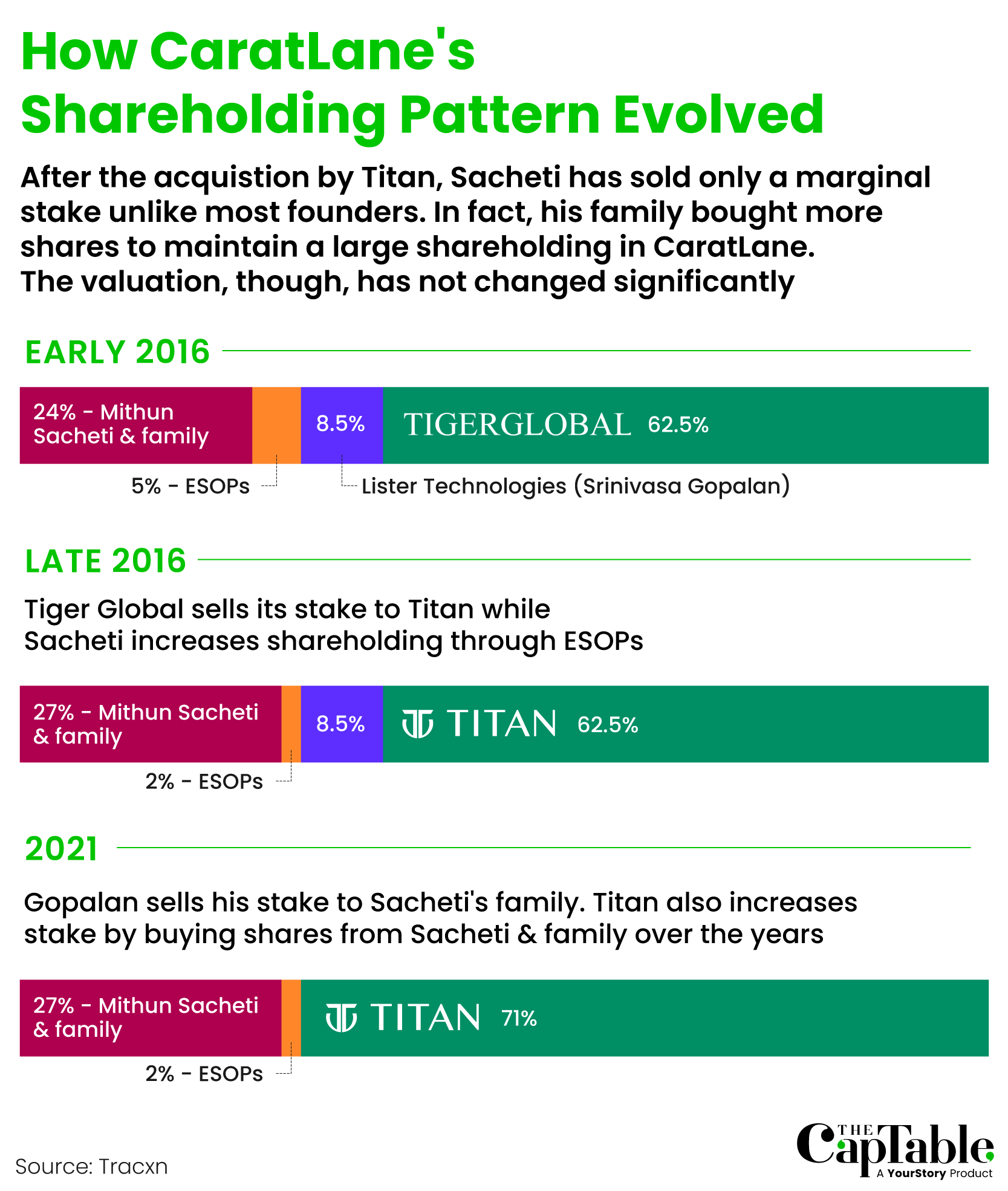

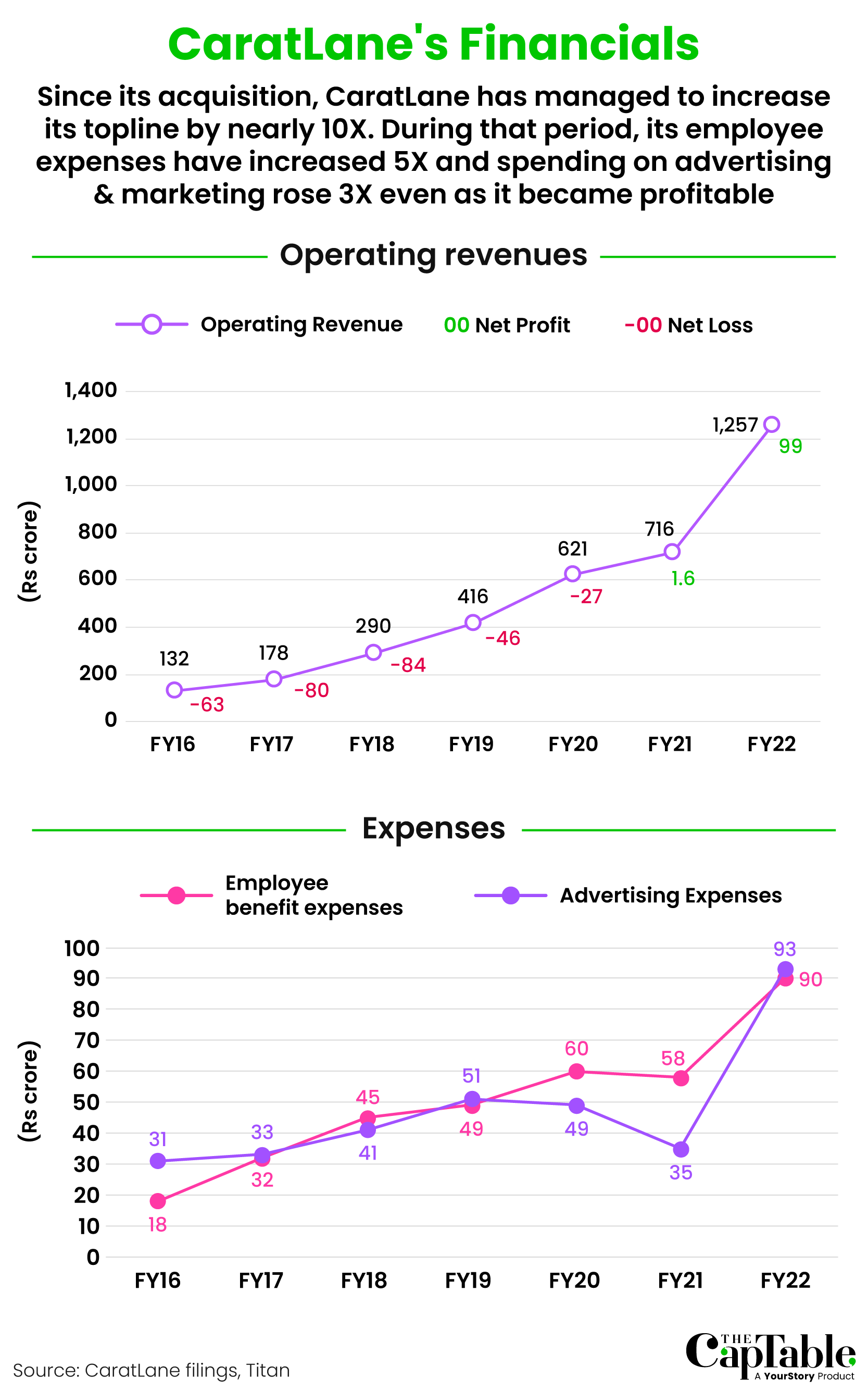

It was against this backdrop that, in May 2016, Tata Group-owned Titan acquired Tiger Global’s entire 62% stake in CaratLane. At Rs 357 crore, the deal was still good enough to give Tiger Global—the primary backer of India’s internet story and the biggest shareholder in Flipkart—a decent return. The New York-based investment firm had invested a total of about Rs 284 crore in the Chennai-headquartered startup. CaratLane, though, saw its valuation drop—from 710 crore ($106 million) in its 2015 fundraise to Rs 575 crore ($86 million). CaratLane had revenues of Rs 141 crore in the year ended March 2016, clocking a net loss of Rs 63 crore.

Six years later, Tata’s faith in CaratLane stands vindicated. The quarter ended June 2022 was the online jeweller’s best quarter ever, with revenues soaring over 200% to Rs 483 crore. That is more revenue in a quarter than it made for the entire year ended March 2019. The company also reported a profit before tax of Rs 26.7 crore for the quarter.

Already, CaratLane is bigger than Titan’s eyewear business, which was launched in 2013 and had revenues of Rs 517 crore in the year ended March 2022. And it is catching up with the watches business, which had revenues of Rs 785 crore in the June quarter as compared to CaratLane’s Rs 483 crore.

Interestingly, CaratLane did all this with Mithun Sacheti, the company’s co-founder, still leading the way as managing director. Sacheti had a three-year contract as a part of the transaction, according to two sources briefed on the matter. Not only is he still in charge, Sacheti and his family still maintain a stake in the company. They even increased their shareholding by buying out the company’s tech co-founder, who wanted an exit after the Titan deal.

Now, with CaratLane emerging as one of the jewel’s in Tata Group’s consumer retail crown, Sacheti is also at a crossroads. Titan wants to buy out the 27% stake held by Sacheti and his family in CaratLane, making the business a fully-owned subsidiary.

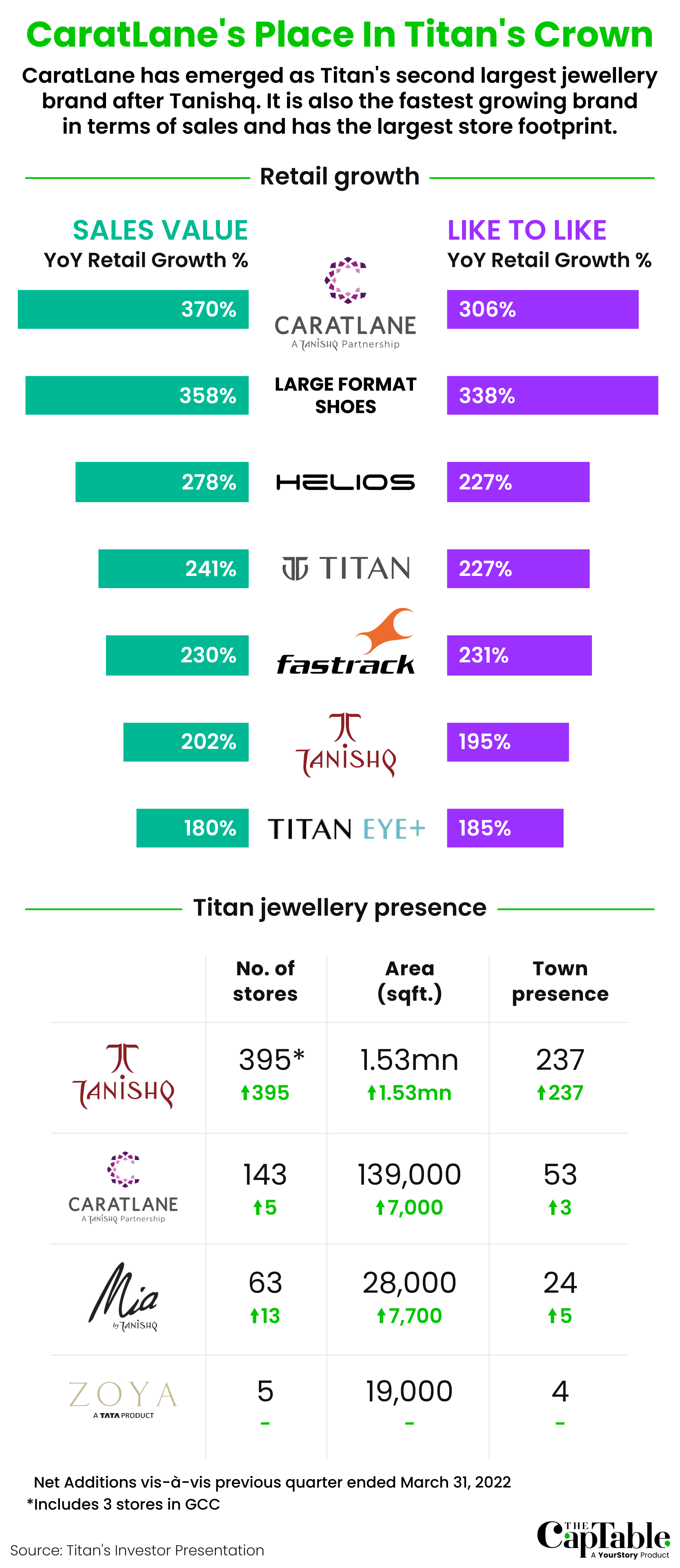

Graphic: Winona Laisram

Discussions about this have been ongoing for nearly two years, centering on the valuation and how the deal could be structured. Brokerages tracking Titan, ranging from Macquarie to JP Morgan, have pegged that valuation of CaratLane between Rs 15,000-25,000 crore.

“There was a conversation on whether the deal will be a cash transaction last year, but right now it is increasingly veering towards a stock-based deal. If that happens, Sacheti and his family will become one of the largest individual shareholders of Titan,” said one of the sources briefed on the matter. Email queries sent to Titan and Sacheti did not elicit a response.

Whether the deal is a cash or stock transaction has not been decided, but whatever the outcome, it would entail a significant valuation re-rating for the business. Given the scale the business has achieved, it is thought this number could cross $2 billion. This would entitle Sacheti and his family to a windfall of over $500 million—whether as cash or shares in Titan—when the buyout happens. This would be one of the most significant instances of wealth creation for an entrepreneur in India’s consumer internet economy since the $1 billion that Sachin Bansal made when Flipkart was sold to Walmart in 2018.

Sacheti’s family has been in the jewellery business for decades. They own Jaipur Gems, one of the luxury brands in the space, which was founded in 1974. Sacheti, too, was part of the family business, getting certified by the Gemological Institute of America. He helped Jaipur Gems expand from Mumbai to South India, opening stores in Chennai and Coimbatore.

CaratLane, Sacheti’s brainchild, was founded in 2007. While Sacheti brought the jewellery business expertise, he roped in Srinivasa Gopalan to bring the technology know-how required to build an e-commerce business. Gopalan had previously served as senior VP at information and communication technology giant Sify.

Sacheti’s background in the jewellery business has been vital to the company’s operations. “He himself is a jewellery designer, so he brings significant understanding in supervising the manufacturing process. In the jewellery business, wastage can kill you. It may look like a small thing but can compound significantly,” said a venture capital investor who had evaluated CaratLane but did not invest in the space.

His knowledge of the space is also what led CaratLane to focus on diamonds rather than gold, which has a lower scope for margins. “The cost of gold is known to everyone, so you cannot play around with it. That is why one needs to really scale up the business and make money on the making charges,” said the investor mentioned above. “But diamonds are different, as no one knows how much they cost, and margins traditionally have been better.”

With the jewellery design and manufacturing already perfected by Sacheti’s family business, all CaratLane needed was a website to collate orders. And freed from the overheads of a high street showroom, CaratLane could sell its high-end diamonds at attractive discounts.

For all its promise, though, CaratLane’s early going was slow. With Flipkart launching around the same time, shopping online was still a novel concept to Indians, and was largely restricted to products like books and electronics.

And unlike online retail verticals like fashion, furniture, and home decor, which saw dozens of venture-funded startups, the jewellery sector did not attract as much capital or new entrants. Accel-backed Bluestone, launched by former Amazon executive and serial entrepreneur Gaurav Singh Khushwaha in 2011, was one of the few rivals to CaratLane that sprung up. There were also players like Juvalia & You, launched by Delhi-based Smile Group, which raised some seed funding but shut down a few years later.

Still, in the midst of India’s first e-commerce funding boom in 2011, the company’s potential caught the eye of Tiger Global. Tiger would become the company’s sole external investor, maintaining that status for the next five years as it invested four more times.

Despite benefiting from Tiger’s benedictions and bankroll, Sacheti had his heart set on bringing Titan onto CaratLane’s cap table. Sacheti was keen on the partnership with Titan as his family business had a long-standing history as suppliers to the Tata Group company. He always kept in touch with Titan, asking them if they would like to invest in each round the firm raised, according to a source briefed on the matter.

But the speed of Tiger Global, led by Lee Fixel at the time, never matched the measured approach of Titan.

By 2015, Sacheti realised that customers were still hesitant to make expensive luxury purchases online. And while CaratLane attempted to alleviate these apprehensions with a ‘try-at-home’ offering, the experiment proved expensive and hard to scale. “In 2015, after he had just raised capital, he decided that retail will be a big part of this business. Omni-channel will be the way to do it,” said a former CaratLane executive.

“The problem that all companies faced in this sector initially was that they were being too innovative in the way customers buy products. When you go back to basics, you are going to be fine,” said Siddharth Talwar, partner at Lightbox Ventures, referring to the offline push by all the players in the space over the last 3-4 years. Lightbox is the largest shareholder in CaratLane rival Melorra, backing the startup when it was a paper plan back in 2016.

While CaratLane started its offline expansion in June 2015, building trust in a new jewellery brand takes decades. This wasn’t a problem that could be solved by spending big on marketing. Sacheti realised that he needed a partner which could instantly gain him the trust of customers across the country.

Titan—which boasted one of India’s premier jewellery brands, Tanishq—was the ideal partner. Fixel, for his part, was open to Titan coming onboard. However, he insisted that Titan’s shareholding be restricted to 26%, something the company refused to entertain.

“That took a little coaxing and convincing. Sacheti told Lee that this is the right thing for the business, and that they (Titan) should have a majority stake because CaratLane needs the trust and name. A few hundred crores is not going to cut it,” said the former executive mentioned above. Fixel—who was busy managing the fate of Tiger Global’s $1 billion wager on Flipkart at that time—finally relented.

For Titan, the deal was about understanding how e-commerce can work in the jewellery space, and getting a team which can execute with a different mindset than what they were traditionally used to. Another driver was Titan’s desire to target younger customers by selling at a lower price-point—between Rs 8,000-10,000—something it could not do with Tanishq’s luxury positioning.

Soon after the deal was announced, there were a lot of questions about how the business would operate. There were obvious areas of synergy, like sourcing, designing, and manufacturing at scale, which could help lower CaratLane’s costs. But given that Sacheti wanted to build out an omni-channel play, the question was whether it made sense to partner with Tanishq stores or sell Tanishq products through CaratLane. Both were very different brands and were targeting customers at different price points. Analysts also worried about the culture gap between Titan and CaratLane’s management teams.

Bhaskar Bhat, Titan’s managing director at the time, was clear from the start that CaratLane should be able to chart out its own destiny and needed to operate autonomously for the business to work. It would continue to operate out of Chennai and continue to remain independent, he said on an analyst call shortly after the deal was announced.

Sacheti was clear from the start about how he wanted to leverage the relationship with Titan. First, he wanted CaratLane to be endorsed as a Tanishq brand, allowing it to benefit from Tanishq’s positive perception. That took Sacheti six months to close. Since then, the CaratLane branding has always been prefixed with “A Tanishq partnership”.

The second synergy Sacheti wanted was in terms of operational efficiency and excellence. This was implemented in several aspects of the business over the years. CaratLane initially started benchmarking its costs—from salaries to marketing to raw materials purchased to taxes—with the more traditional business. And then the company started working to improve these metrics.

While most e-commerce companies equate increasing the number of stock keeping units (SKUs) with scaling, CaratLane has been doing the opposite. From a peak of more than 8,000 SKUs, CaratLane now has just around half that. CaratLane did this by prioritising the fastest selling SKUs and cataloguing the occasions for which people need jewellery, allowing the business to minimise inventory and supply chain expenses.

Graphic: Winona Laisram

Having a major benefactor like Titan has also given CaratLane access to cheaper debt. Since its borrowings are guaranteed by Titan, CaratLane has been able to achieve an AA/A1 rating from credit rating agencies like Crisil and ICRA, helping it borrow at cheaper rates. The company has raised debt through instruments like commercial papers, term loans, and working capital facilities. Since the acquisition of the company in 2016, Titan has only made a further equity investment of just Rs 100 crore in the company at a valuation of Rs 1,100 crore. At the same time, revenues have increased from Rs 141 crore in the year ended March 2016 to Rs 1,255 crore in the year ended March 2022.

At the same time, CaratLane opted to expand its network of offline stores through franchising, allowing it to grow this channel with minimal capital outlay. This is a trick it picked up from Titan. Launched in 2017-18, franchisees currently account for 20-25% of CaratLane’s stores. In these stores, it doesn't have to spend upfront on construction or on inventory. However, CaratLane has limited the number of franchisees, allowing it to maintain quality. Several of these franchisee owners also own Tanishq franchises, with many CaratLane stores located close to Tanishq outlets.

Graphic: Winona Laisram

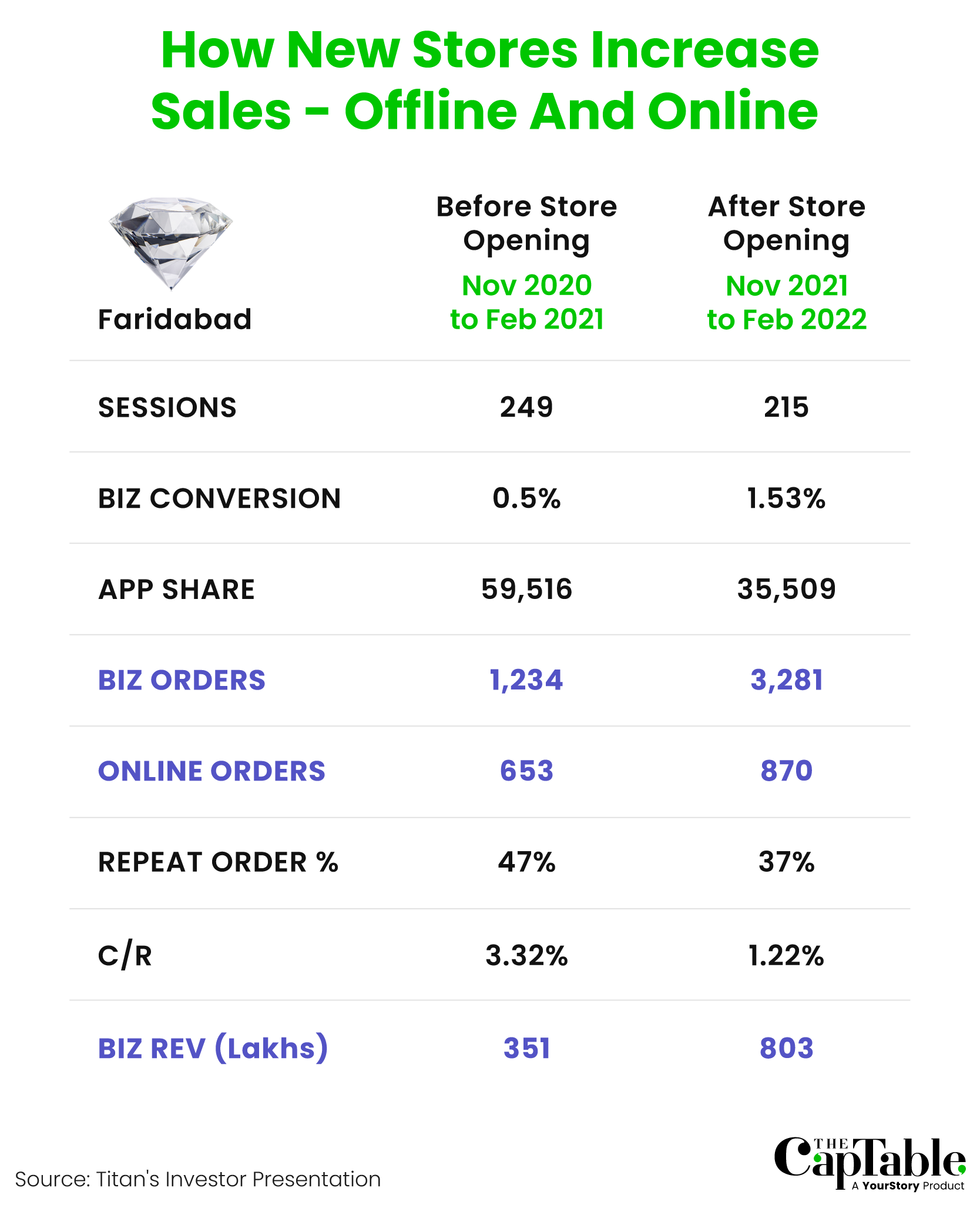

During Titan’s investor day earlier this year, Sacheti took the example of a store opening in Faridabad to illustrate the impact offline stores have.He said that while the total number of customer sessions did not increase significantly, conversions increased 3X.

This approach began showing results early on. For instance, in the quarter ended December 2018, CaratLane saw overall growth of 43%, largely driven by its stores. Its online business in that quarter grew at just 13%, according to information disclosed by Titan. As of now, about 70% of CaratLane’s sales were done offline. The online channel is far from redundant, though. Over 80-85% of the sales are online-influenced transactions, with only 15-20% of the sales coming from a straight walk into the stores, according to the company’s investor presentations.

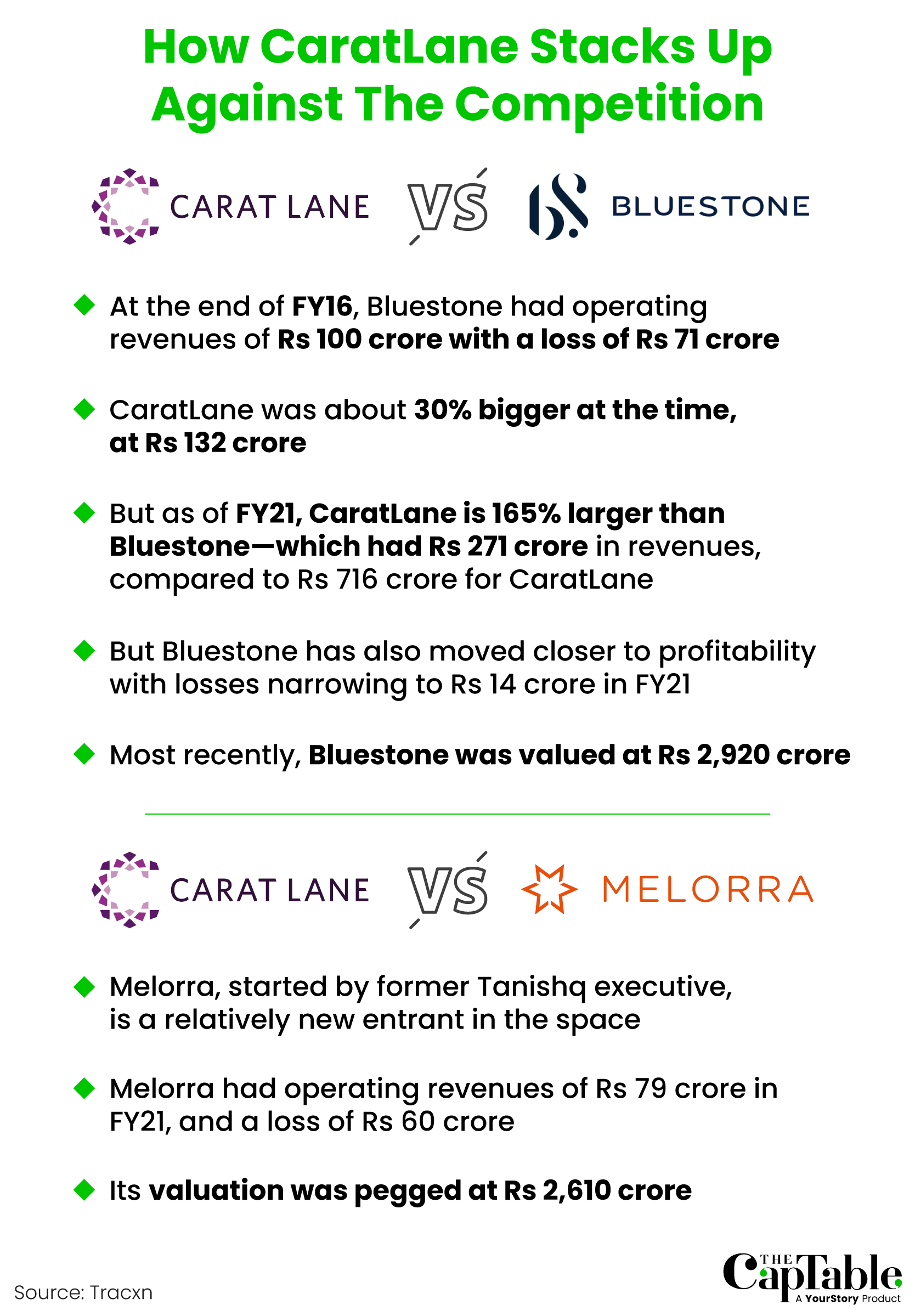

By shifting to an omni-channel approach early and aggressively expanding offline, CaratLane has stolen a march on similarly-funded competitors. For instance, BlueStone had revenues of Rs 103.4 crore for the year ended March 2016—the year CaratLane clocked Rs 141 crore in revenue. That is a gap of just 37%. Five years on, CaratLane’s Rs 723 crore topline was nearly 3X that of Bluestone’s Rs 270 crore.

“Mithun played the game of omni-channel very well. And also in terms of supply chain, they have built the operations well to manufacture at the backend and then ship the products. On the other hand, the Bluestone founder spent two years convincing the company board to launch offline stores,” said the venture capital investor mentioned earlier.

Its competitors have also followed suit. While Melorra began operations in 2017, it launched its first offline store in 2020 with an aggressive expansion plan going forward. While about 20% of Melorra’s revenue today comes from its 25 stores, the plan is to increase this to 50% as it adds more outlets.

Graphic: Winona Laisram

CaratLane is also getting more aggressive with a record number of new stores planned. In a note on the company, Crisil stated that CaratLane could achieve sales of Rs 1,800-2,000 crore in the year ending March 2023, driven primarily by the 90 new stores it is expected to add. “The expansion in stores is expected to be achieved with moderate-to-low capital expenditure (capex) as most of them would be smaller format and franchise-based stores,” read the note.

According to Talwar of Lightbox, it is not just CaratLane which is scaling well. The overall demand in the jewellery sector has been robust. Titan saw a 204% increase in revenues—touching Rs 7,600 crore—for the jewellery business during the quarter ending June 2022, as compared to the same period last year. In the same period, Kalyan Jewellers saw operating revenues of Rs 3,332.63 crore—a 104% jump compared to the year-ago period.

Melorra has also crossed $100 million in annual recurring revenues, according to Talwar. “No one has as much per-square-foot revenue as compared to jewellery companies in malls or high streets. I am actually surprised that more jewellery startups haven’t come up.”

A recent report by JP Morgan said that CaratLane is a “diamond in the making” for Titan, accounting for about 5% of its market capitalisation. Among the jewellery business, CaratLane is already the second largest brand after Tanishq in terms of retail footprint, with 143 stores as compared to the latter’s 395.

CaratLane has also expanded its retail footprint a lot faster than some of Titan’s older brands like Mia, which it competes with in terms of market segment and price point. At the end of the year ended March 2018, both CaratLane and Mia had 36 offline stores. But as of June, Mia lags far behind with just 63 stores.

Analysts have asked the Titan management if multiple brands could end up eating into each other's revenues. In February, Ajoy Chawla, the head of Titan’s jewellery business, said that its jewellery brands—Tanishq, CaratLane, Mia, and Zoya—together account for 6% of India’s jewellery market. This leaves the brands plenty of room to grow without treading on one another’s turf.

Graphic: Winona Laisram

With CaratLane’s place in Titan’s jewellery pantheon firmly secured, Sacheti has earned the right to ride off into the sunset. Even though he continues to serve as MD & CEO, a lot of the company's day-to-day operations are now being overseen by Avnish Anand, CaratLane’s chief operating officer. Anand was CaratLane’s first employee and, according to his LinkedIn profile, was awarded the co-founder designation in 2016.

Sacheti’s focus has instead shifted to Oro Money, a gold loan business he co-founded in 2020. Oro has raised Rs 36 crore from the likes of Binny Bansal-backed 021 Capital, and PremjiInvest, the family office of Wipro billionaire Azim Premji. Freshworks’ CEO and founder Girish Mathrubootham is also an investor.

But before Sacheti can truly change tracks, there is still the matter of divesting from CaratLane since Titan’s key subsidiaries are typically wholly-owned. The question now is about the valuation that CaratLane currently commands.

In March 2019, the last time Titan infused funding into CaratLane, the startup’s valuation stood at Rs 1,110 crore. Its closest rival Bluestone, which was expected to finish the year ended March 2022 with revenues of Rs 500 crore received a valuation of Rs 2,920 crore in May when it raised Rs 75 crore from Hero Group’s Sunil Munjal. Bluestone is reportedly considering going public at a valuation between Rs 12,000-15,000 crore.

“It is a question of how much contribution margin CaratLane has,” said the venture capital investor mentioned above. CaratLane has seen its EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes) margins improve steadily. From a -2% margin in the year ended March 2020, the figure stood at 5% in the year ended March 2022. For the latest June quarter, it stood at 7%.

Given the market leadership position it has, many are benchmarking the valuation of CaratLane to eyewear retailer Lenskart as well. Lenskart has always been getting 10X of projected revenues, according to the venture capital investor mentioned earlier. Based on CaratLane’s expected revenues of Rs 1,800 crore for the year ending March 2023, this would net it a valuation of Rs 18,000 crore. Not too shabby for a business in which Titan has invested just Rs 505 crore in equity thus far.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

Be the smartest person in the room. Choose the plan that works for you and join our exclusive subscriber community.

Premium Articles

4 articles every week

Archives

>3 years of archives

Org. Chart

1 every week

Newsletter

4 every week

Gifting Credits

5 premium articles every month

Session

3 screens concurrently

₹3,999

Subscribe Now

Have a coupon code?

Join our community of 100,000+ top executives, VCs, entrepreneurs, and brightest student minds

Convinced that The Captable stories and insights

will give you the edge?

Convinced that The Captable stories

and insights will give you the edge?

Subscribe Now

Sign Up Now