It wasn’t long ago that the Indian startup ecosystem was worried that some of the top new-age companies were shifting base to geographies such as Singapore, Dubai, and the US for faster fundraising and more favourable taxation norms.

Things, however, are starting to change, albeit slowly, at least for growth-stage fintech and consumer internet startups who now want to move back to India.

PhonePe, the payments major that Walmart acquired as part of its acquisition of Flipkart, is the first major company to do this. It is shifting its registered headquarters from Singapore to India. PhonePe is also currently in the process of demerging from Flipkart and raising a new round of funding, as The CapTable reported previously.

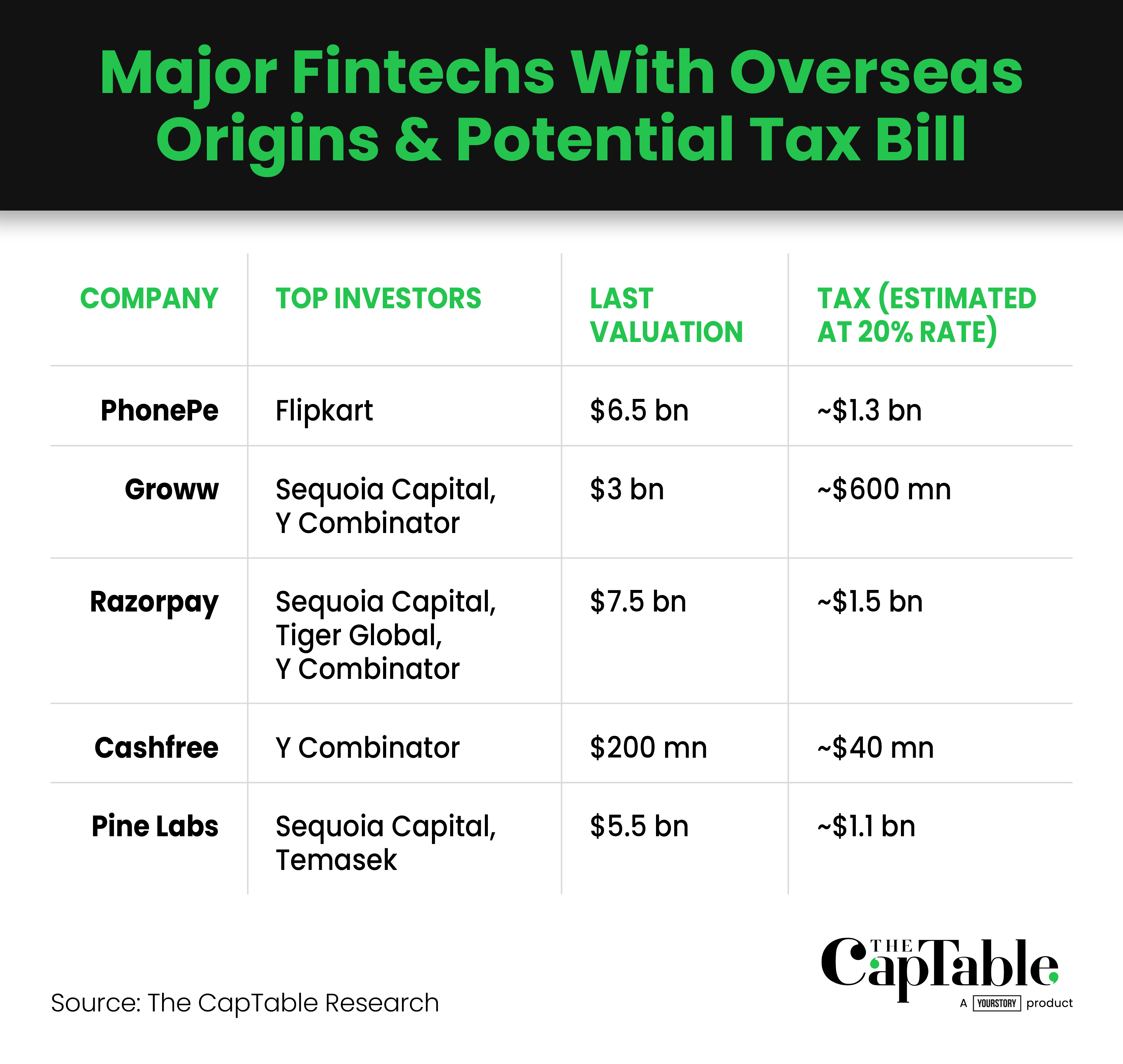

The move back, however, comes with a significant catch. PhonePe’s shareholders must cough up about $1.2-1.3 billion in taxes as a part of the flip back to India, two sources familiar with the developments said. These investors are liable to pay long-term capital gains tax as a result of the move back to India. The long term capital gains tax rate could be 20% with indexation, lawyers say.

“The first player out of the gate always gets bloody,” quipped one of the sources mentioned above.

Even as PhonePe charts a course back to where it was born, several others, including unicorn payments giant Razorpay, are exploring moving their registration from overseas to India. These startups, as well as others looking to follow in PhonePe’s footsteps, will have to navigate the same taxation hurdles. Some of the major fintechs with overseas parent companies are Razorpay, Groww, Cashfree, and Pine Labs.

As a part of PhonePe’s return to India, there are series of transactions underway in order to change the shape of the company’s cap table. First, Flipkart will not be a shareholder in Phonepe Private Limited, which will be registered in Mumbai, after the change. Instead, Flipkart’s key shareholders, such as Walmart, Tiger Global, and Softbank Vision Fund, will get a direct stake in Phonepe. This will mirror their holdings in Flipkart, according to people briefed on the matter.

PhonePe’s move is the culmination of a years-long process, which first gained momentum in 2019-20, to unlock value in the payments business.

This has created a tax liability for PhonePe shareholders, many of whom are liquidating part or all of their stake in order to make these payments. Several smaller investors like Accel, which have less than a 1% stake, are selling their entire stake as part of the transaction, according to the sources mentioned above.

“One of the ways, amongst the many available options, is for companies to internalise into India via a share swap. If a share swap is undertaken, there is a possibility of capital gains tax on the investors. If the share swap is at current fair market value, which may be higher than the allotment price, then the delta is taxed as capital gains,” said Sharda Balaji, founder of NovoJuris, a law firm specialising in corporate law, private equity, fund formation, and investments.

“There can be many other ways that the internalisation of business can be undertaken, such as a slump sale, asset purchase, etc. However, the bigger challenge is always the reflection of the cap table while internalising with the least tax impact,” she added.

For many venture capital funds, it becomes a lot more complicated. Funds typically don’t have a corpus to pay taxes on investments on which they haven’t booked profits by actually realising cash. Most of the gains are notional for them.

With the funding environment turning more bearish, investors are also uncertain about valuation corrections of companies since many could be forced into downrounds. If this were to happen, it’s difficult for investors to gauge how much of their notional profits will actually be realised.

For instance, a fund may be sitting on an investment which has yielded a profit of $100 million, according to the boom market valuations of 2021. However, the fund may actually only be able to reap $50 million once they sell shares over the next few years, explained one investor.

“Investors are also happy to pay the tax, but the fact is that these are notional gains and not cash in hand. The tax, though, needs to be paid upfront. If the government comes up with a scheme to defer taxes, then it can be helpful,” said this investor. They have multiple portfolio companies looking to change registrations from overseas to India.

PhonePe is helped by the fact that its cap table is largely dominated by Walmart, a corporate entity, and other balance sheet investors such as Tencent and sovereign wealth funds such as Singapore’s GIC and Qatar Investment Authority.

Most of the companies considering shifting back to India are in the fintech space.

One key reason for this is that financial services is a highly-regulated industry, with the likes of Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and capital markets regulator Sebi making it their mission to safeguard customers. This has meant cracking down on fintechs and increasing regulations which protect consumer interests, which we have covered here, here, here and here.

“With the help of DLG (digital lending guidelines), the government has ensured that players who want to create some profitable businesses need to set up Indian entities to carry out regulated businesses like insurance and lending,” said Pratekk Agarwaal, founder of fintech advisory firm Trutes Advisors.

Agarwaal explained that laws and regulations are being designed so that the revenues earned from these businesses need to be re-invested in India itself. These companies must also transparently show the legitimacy of incoming funds via the foreign direct investment (FDI) route when seeking licences, including for NBFC status.

In 2020, startups such as BharatPe, Jupiter, and CarDekho faced issues in getting an NBFC licence from RBI due to greater scrutiny of investments from China, according to a Times of India report. There are other broader changes in policy driving this change as well, especially for newer startups. Many companies were incorporated in overseas jurisdictions, while all their operations were in India, and run through step-down subsidiaries.

“With the new Foreign Exchange Management (Overseas Investment) Rules, 2022, founders will have to rethink this more carefully, especially if there are any Indians on their cap table. This is because of the robust definition of “Control”, which, apart from other aspects, says that if there are Indian individuals holding more than 10% voting rights in the overseas company, then such companies cannot have a subsidiary,” said Balaji.

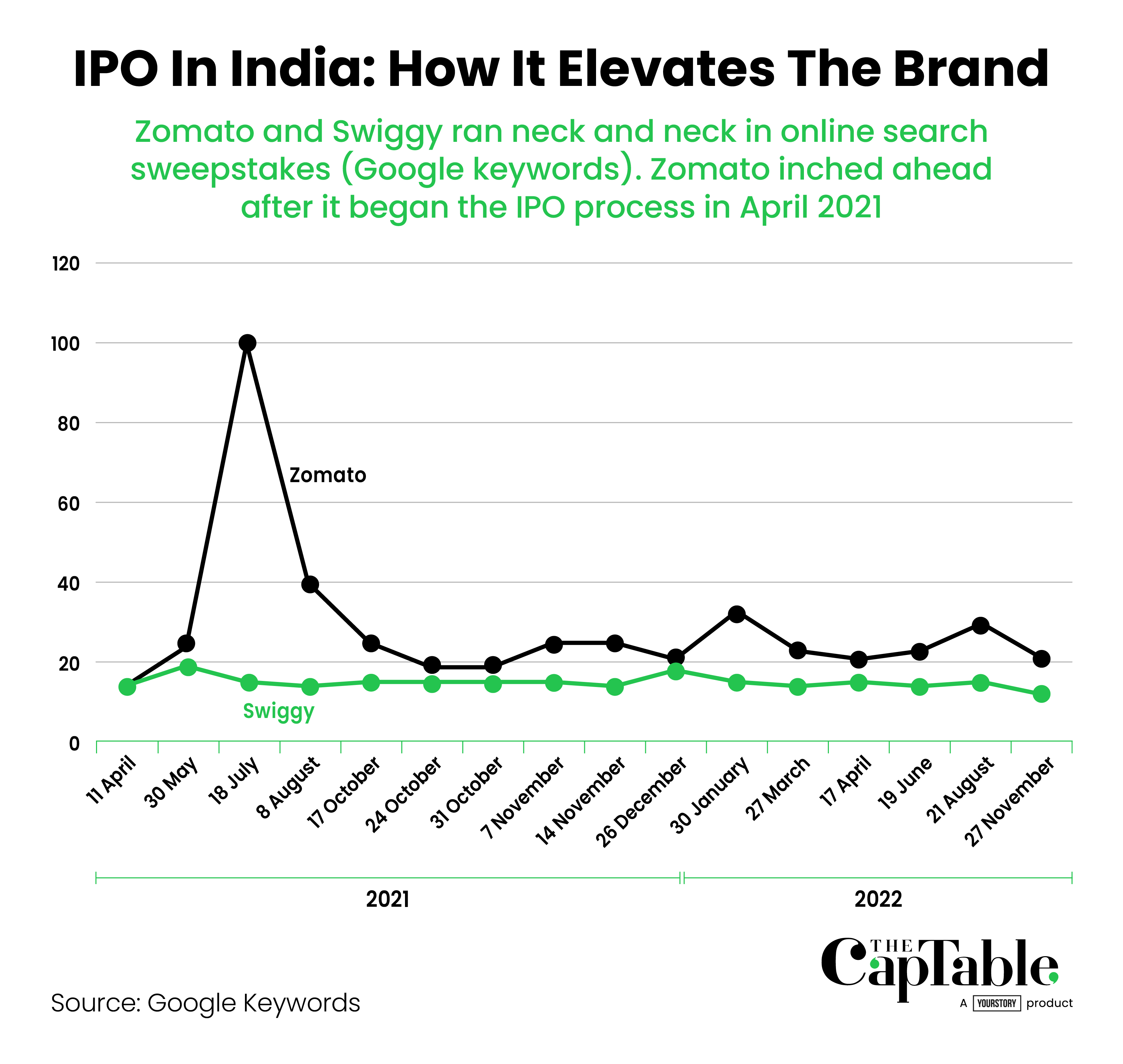

There is also a growing realisation among investors and entrepreneurs that the Indian capital market has enough capacity to absorb large initial public offerings (IPO) and also has a growing base of domestic investors.

Many feel that going for smaller IPOs—with valuations below $5 billion—in the US market are not likely to attract as much investor interest, according to an entrepreneur considering flipping back to India. These IPOs will attract more investor interest in India.

This sentiment is also bolstered by the fact that a lot of the business models emerging in both fintech and the consumer internet space are more specific to India, and don’t have an exact parallel in the US market.

“For fintech and several India-specific businesses, capital markets (in the US) will have to spend a lot of time understanding their business nuances. Their incentives are not aligned with this level of detail. A standard business like MakeMyTrip, which has a global use case, they will understand, but for India-specific [companies], they won't even bother to understand for a few million dollars,” said the entrepreneur quoted earlier.

Another factor is that companies listing in India are attracting much higher valuation multiples as compared to their peers in the US market.

Another factor is the brand-building necessary in the lead up to an IPO for companies. “For consumer companies that list in India, there is already hype and buzz that gets created. In some sense, that becomes free marketing for the companies, which is a big expense that they don’t want to miss out on,” said the investor quoted earlier.

For many entrepreneurs, considerations also include issues like potential lawsuits, however frivolous, for not meeting guidance on revenues and other metrics. The entrepreneur quoted earlier pointed to Freshworks as an example of this. The software-as-a-service giant has been sued in the US for making “false and misleading statements.”

“No listing has done well. Companies are getting sued on guidance. You have to ask yourself, is it worth it?,” said this entrepreneur, explaining why Indian-born companies are keen to return home, even if it means biting the taxman’s bullet.

In addition, access 50+ archived articles and 3 new articles every month

Sign In

Got a tip? If you have a lead we should be chasing at The CapTable, write to us at [email protected]

Join our community of 100,000+ top executives, VCs, entrepreneurs, and brightest student minds

Convinced that The Captable stories and insights

will give you the edge?

Convinced that The Captable stories

and insights will give you the edge?

Subscribe Now

Sign Up Now