Key Takeaways

Every morning at 8 AM, shortly before the Vasco Da Gama-Patna Superfast Express pulls into Patna, the capital city of Bihar, e-rickshaw driver Nitish Kumar begins his day. Kumar and his six brothers head to Katayayani Motors, a used car dealership in the northern Patna neighbourhood of Rajeev Nagar. Here, they swap the batteries of their e-rickshaws, drained from ferrying passengers around the previous day, for freshly charged ones.

Behind the shop floor at Katayayani Motors is a small room where around 25 batteries are continuously plugged into wall sockets. Another two dozen-odd fully-charged batteries sit behind the shop counter, awaiting their turn to power an e-rickshaw or an e-scooter. Two men routinely inspect the area to ensure everything is in order.

After six to eight hours of ferrying travellers from the train station to various parts of the city, Kumar and his brothers return to Katayayani Motors to do a quick, free recharge of their batteries, before resuming work for another 2-3 hours.

For Kumar and his brothers, charging electric vehicle (EV) batteries at home doesn’t make sense. “We live in a small house with two sockets. Where will we charge so many batteries?”. Formal charging stations, meanwhile, are a facility in short supply—not just in Patna, but in cities and towns across the country. “There’s no place in Patna to put charging stations. In places where they are present, people steal electric lines and try to charge random household batteries, so no one wants to put charging stations here,” quips Kumar.

Katayayani Motors solves multiple problems for Nitish and others like him. It’s cheaper than charging at home—just Rs 100 to swap a drained battery for a fully charged one. It’s convenient, ensuring they never have to worry about range since a fully charged battery is always available when needed. And the cherry on top, the car dealership’s proprietors often allow them a quick, free top-up in the evenings.

Katayayani is just one of many such small businesses across both Patna and India that have begun catering to India’s nascent but steadily growing EV wave, ensuring reliable and accessible energy solutions for both commercial and passenger EVs.

These businesses range from vehicle resellers and auto repair shops to stores selling auto parts and components. The CapTable spoke with at least 12 of them across Patna, Lucknow, Kolhapur, Allahabad, Mangaluru, and Udaipur, with each estimating they personally knew of at least 30 other similar operations.

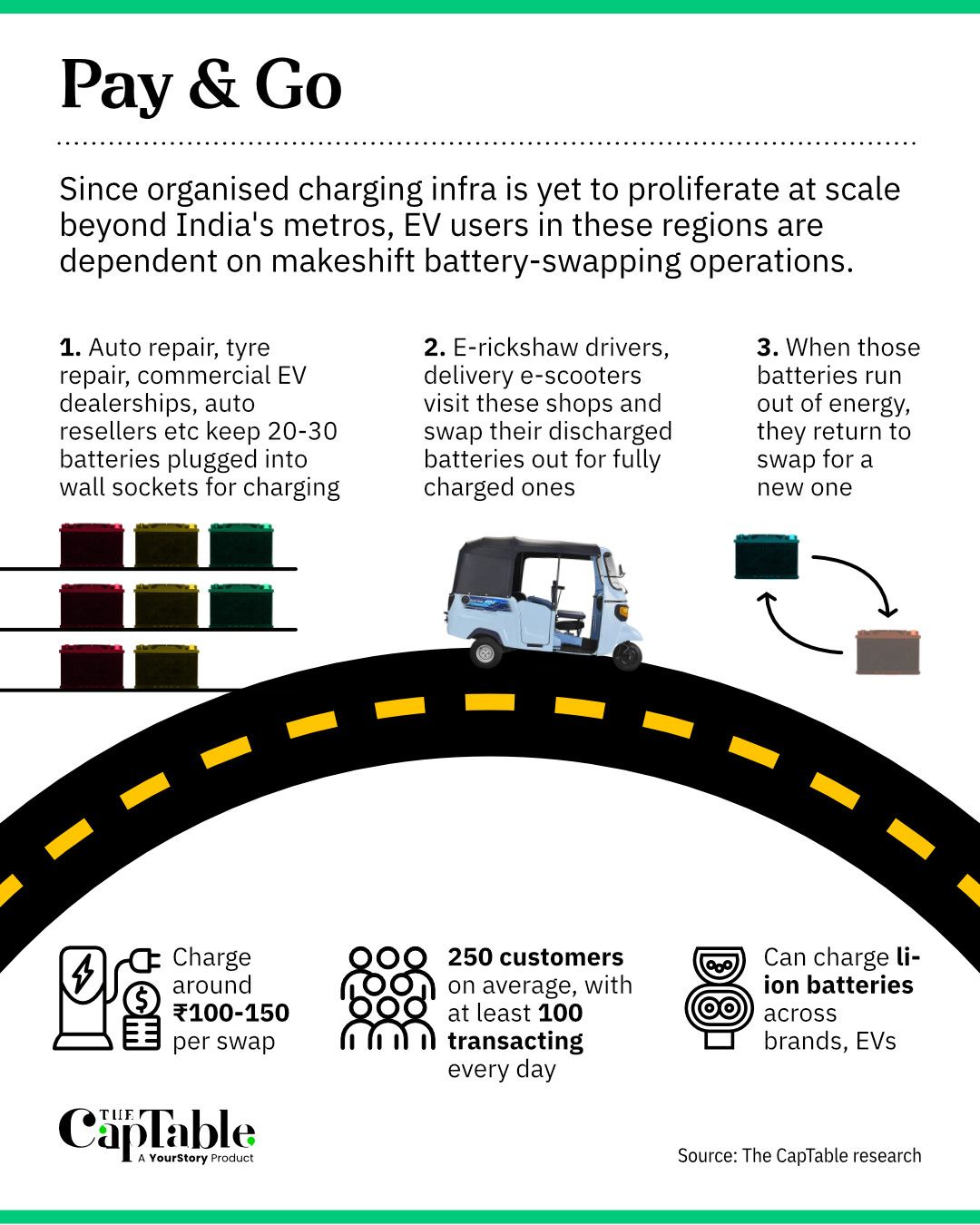

There are several commonalities in the way these informal, semi-structured ‘battery-swapping’ shops operate. Typically, they serve e-rickshaws and e-scooters used by delivery agents and last-mile services. Each shop generally maintains 35-40 batteries on continuous charge, with additional batteries ready for immediate deployment. The fee for each swap generally ranges from Rs 100-150.

On average, most shops handle 70-80 swaps per day, generating revenue of nearly Rs 10,000 and incurring electricity costs of around Rs 2,000 per day, leaving them with a tidy net profit of Rs 8,000. Larger establishments such as auto repair workshops operate more expansive setups, while smaller puncture repair shops offer 10-15 batteries, at least, the 12 operators told The CapTable.

These operations have allowed India’s EV revolution to go beyond big metros, making electric mobility a viable option in smaller towns and cities as India’s formal charging infrastructure plays catch-up.

Infographics by Sharath Ravishankar

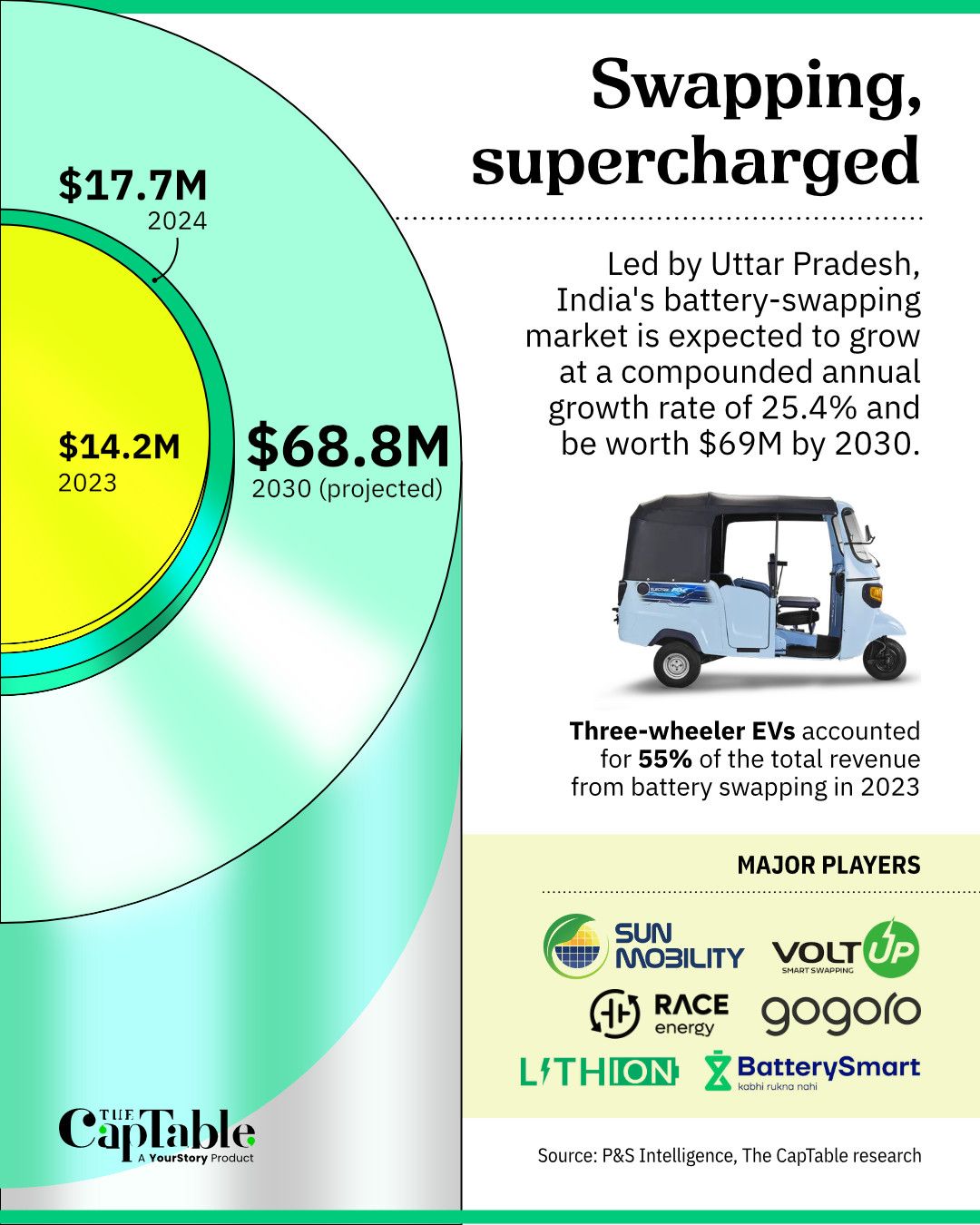

According to research by market intelligence firm P&S Intelligence, India's formalised battery-swapping market is currently valued at $17.7 million.

At present, the ecosystem is led by private equity-funded players such as Battery Smart, RACE Energy, and Taiwan’s Gogoro, which have launched self-service battery-swapping stations and offer either subscriptions or pay-as-you-go options.

The current infrastructure rollout is primarily concentrated in metropolitan cities and larger urban centres such as Delhi NCR, Bengaluru, and Mumbai. Some tier-2 cities such as Cochin and Pune are also seeing increased investment and a growing number of swapping stations to cater to the growing popularity of EVs in these geographies, according to recent data and ongoing conversations with the founders of some battery-swapping startups.

This hyperfocus on metro areas has inadvertently sidelined several substantial cities that have actively adopted EVs. For instance, Uttar Pradesh stands as the leading adopter of EVs. However, outside of the state’s capital of Lucknow, there is a conspicuous dearth of battery-swapping stations, even in prominent EV-enthusiastic cities such as Varanasi, Agra, and Kanpur.

Company executives blame everything from the lack of government support and energy supply issues to expensive real estate for why they’ve stayed away from setting up stations in these regions.

“For a six-by-six-square-foot space in Lucknow, you have to shell out an average of Rs 2-2.5 lakh. Real estate is expensive, which makes setting up swapping stations a very capital-intensive activity. Of course, we’d love to be everywhere, but we have fiduciary responsibilities to our investors, so we can’t expend so much capital,” says the founder of a prominent battery-swapping company.

For smaller operators such as Patna-based Katayayani and KK Motors this presents a window of opportunity. Kaif Ahemad, the owner of KK Motors in Patna, tells The CapTable that he has a total of 250 customers, out of which he services at least 100 daily.

“This business is pretty profitable. You make a one-time investment in the batteries, and then you get a three-year warranty from the manufacturer, so they handle any issues. Even when the battery's done, it still has resale value as a second-life battery, which usually ends up as scrap or used for energy storage,” he says.

His battery-swapping clients are primarily individual drivers who learn about his service through word-of-mouth, along with small-to-medium-sized fleet operators who partner with him exclusively. In the past, he has also hired people to market this specific service, even though his main business is reselling vehicles.

For a lot of these establishments, the revenue from battery-swapping is just a fringe benefit. Most say that offering fully recharged batteries is the easiest way to lure in potential customers for their other services, such as auto repairs or future vehicle purchases.

Atal Singh, the owner of Friends Automobile Services in Lucknow, says that his battery-swapping service has helped him build a good standing with hundreds of e-rickshaw drivers in his neighbourhood, who now also turn to him for repair and maintenance services.

Shri Balaji, an e-rickshaw dealer in New Delhi, says he has landed contracts worth lakhs of rupees to supply EVs to fleets, and it was all because of his battery-swapping service, which helped him build relationships with the owners of these fleet companies. The company told The CapTable that it has also helped fleet operators access subsidised loans through its partnerships with manufacturers, creating an even more conducive environment for EV adoption to become affordable.

On the other side of the equation, fleet operators and individual e-rickshaw and scooter owners enjoy two major advantages. The greatest benefit, they say, is that the informal battery-swapping network eliminates range anxiety—a significant obstacle in EV adoption.

“Once you have an arrangement with these shops, you can be assured that even if you run out of charge, you won’t have to lose half a day’s wages because of not being able to operate the vehicle,” Manu Rana, a six-seater e-rickshaw driver in Jaipur, says. When asked about the barriers to accessing digital battery-swapping stations like those operated by Gogoro, Sun Mobility, or Battery Smart, Manu said their limited availability is a major issue.

“The few swapping stations in Jaipur are really far out. You usually have to take a 10-12-kilometre detour to reach them. Even then, they might be down due to power cuts or the batteries aren’t available because they’re being diagnosed,” he adds.

The other significant advantage these informal operations provide is allowing EV operators to sidestep the outright ownership of batteries, which amounts to ~40% of the total cost of an EV. Several of these shops have even evolved into crucial hubs for fleet operators, serving not only as battery-swapping stations but also as strategic points for expanding or liquidating their vehicle inventories.

Suresh, a manager at Gayatri Tours, a rickshaw fleet operator in Kolhapur, Maharashtra, notes that his company’s alliance with local resellers, facilitated by their battery-swapping services, has also enabled him to offload vehicles at significantly better rates than if they had managed the sales independently or through unfamiliar parties.

“We go to them (informal battery-swapping players) whenever we need to sell our rickshaws and they always give us really good rates and keep very little commission for themselves,” he says. “We’ve also purchased from them in the past and they’re generous with credit and repayments.”

Infographics by Sharath Ravishankar

Even though these operators are enabling electric mobility adoption in regions where charging infrastructure isn’t present or inadequate, formal and VC-funded tech companies in the battery-swapping spaces view this unorganised market with caution.

Their main issue with the system—apart from losing market share and money to them—is the lack of safety measures involved. “We’ve poured hundreds of thousands of dollars and untold hours into safety features to prevent battery malfunctions or worse, explosions. Each swapping station is equipped with failsafes to isolate faulty batteries and prevent fires. Unfortunately, the unorganised sector often neglects these safety measures,” says a member of the Indian Battery Swapping Association (IBSA). “With batteries, things can go from bad to worse in a matter of minutes,” the source quoted above adds.

Indeed, when The CapTable visited one such shop in Bellandur, Bengaluru, we saw that the batteries were stored without any temperature regulation. More alarmingly, there were no fire extinguishers or fire retardant materials present on-site.

“They (safety indicents) have never happened to date. We have someone to check on batteries regularly so that they don’t overheat or overcharge. We also have power surge protectors so that electricity cuts and resumptions don’t hamper the batteries,” insists the owner of the shop, who declined to speak on the record.

The IBSA member concedes that e-rickshaw and two-wheeler delivery drivers have been forced to depend on the unorganised sector for their battery-swapping needs because of the lack of formalised, tech-supported stations. To further compound the problem, at least 70% of the battery-swapping stations today are concentrated in metros, leaving tier-II and lower cities to find innovative solutions to support their EV adoption.

While the government has taken some rudimentary steps to incentivise EV charging infrastructure—such as discounts on real estate and chargers, priority regulatory approvals, expedited electricity connections, and subsidised electricity consumption rates—much more needs to be done, particularly with a focused approach on advancing battery-swapping solutions.

For one, battery-swapping services providers–both formal and informal–have called for the standardisation of battery safety protocols, along with incentives to develop a robust battery-swapping infrastructure and mechanisms to put guardrails in place to prevent accidents. “If manufacturers make safer, heat-resilient batteries, it won’t be a problem for anyone and more people will adopt EVs,” says Shaik Salauddin, National General Secretary of the Indian Federation of App-Based Transport Workers (IFAT).

Another is legitimising and regulating the unorganised sector so that it complies with safety requirements and no longer operates in the shadows. “The government should look at us as enablers of EVs, serving EV adoption at a grassroots level. They should encourage more such shops like us so that more rickshaws become electric,” says Sathish Golla, owner of Shriram Tyres, a tyre and auto repair shop in Mangaluru, Karnataka.

Golla adds that incentives for the informal sector to build basic safety measures into their operations–fire extinguishers, air conditioning units where the batteries are plugged in–could not only enhance the reliability and safety of these swapping stations but also better the shelf life of batteries and build customer confidence.

Until that happens, the best hope for EV users in smaller cities and towns is that they could gain access to formal swapping stations thanks to burgeoning partnerships between battery tech companies and ubiquitous and deep-pocketed oil and gas players.

Earlier this year, for example, Sun Mobility signed a joint agreement with Indian Oil to set up 10,000 battery-swapping stations across over 40 Indian cities. Mooving, another company in the space, has partnered with HPCL to set up infrastructure across 22,000 petrol pumps across India. HPCL has also signed a similar agreement with Gogoro.

Unless these initiatives gain a head of steam, though, unorganised battery-swapping operations will remain a crucial bridge for India’s EV transition.

Edited by Ranjan Crasta

Convinced that The Captable stories and insights

will give you the edge?

Convinced that The Captable stories

and insights will give you the edge?

Subscribe Now

Sign Up Now