Key Takeaways

Just a few years ago, India’s B2B e-commerce platforms were investor darlings. During their peak in 2021, 10 companies in the space—including the likes of Udaan and Moglix—raised upwards of $100 million, according to a report from global consulting giant PricewaterhouseCoopers. That year, the B2B e-commerce space as a whole raised a shade over $3 billion.

This bullishness was largely the result of investors being sold on the idea of technology-enabled organised players disrupting India’s sprawling offline grocery market. With over 12 million mom-and-pop stores, or kiranas, and a further 1 million wholesalers and distributors serving as the connective tissue between brands and shops, India’s offline grocery market was worth around $523 billion at the start of this decade, states a report published by market intelligence platform Statista.

India’s B2B e-commerce players, though, haven’t been able to build on their strong beginnings, struggling to chart a course to profitability even as funding has gone from a deluge to a drip.

Take Udaan, for instance. In 2021, it raised a $280 million Series D round that pegged its valuation at $3.2 billion. Flush with capital, the Bengaluru-based company—originally a pureplay online B2B marketplace—pivoted to an inventory-led model. But while its operating revenue surged to nearly Rs 9,900 crore in the year ended March 2022, it was operating at an EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortisation) margin of -27%. Consequently, it clocked losses of Rs 3,030 crore.

The company has since undergone several rounds of layoffs and scaled down its operations considerably. Having raised $350 million in debt in 2022, it is reportedly looking to raise another $150 million of equity funding in what is expected to be a down round. The likes of social commerce unicorns DealShare and Meesho have also given up on their B2B e-commerce plays.

Even the mighty Reliance Retail isn’t immune to the vagaries of the B2B e-commerce space. Its leadership was reportedly concerned about the burn-intensive nature of their e-commerce venture JioMart’s B2B operations. The platform halted operations in August ahead of being merged with Reliance Retail’s latest acquisition, Metro Cash and Carry.

But amidst the broader rout of e-commerce B2B companies, one player stands out—ElasticRun. While the Pune-based startup also made hay during the funding sunshine of 2021—turning unicorn after a $330 million fundraise led by SoftBank and Prosus—it has avoided the pitfalls that have ensnared many of its peers.

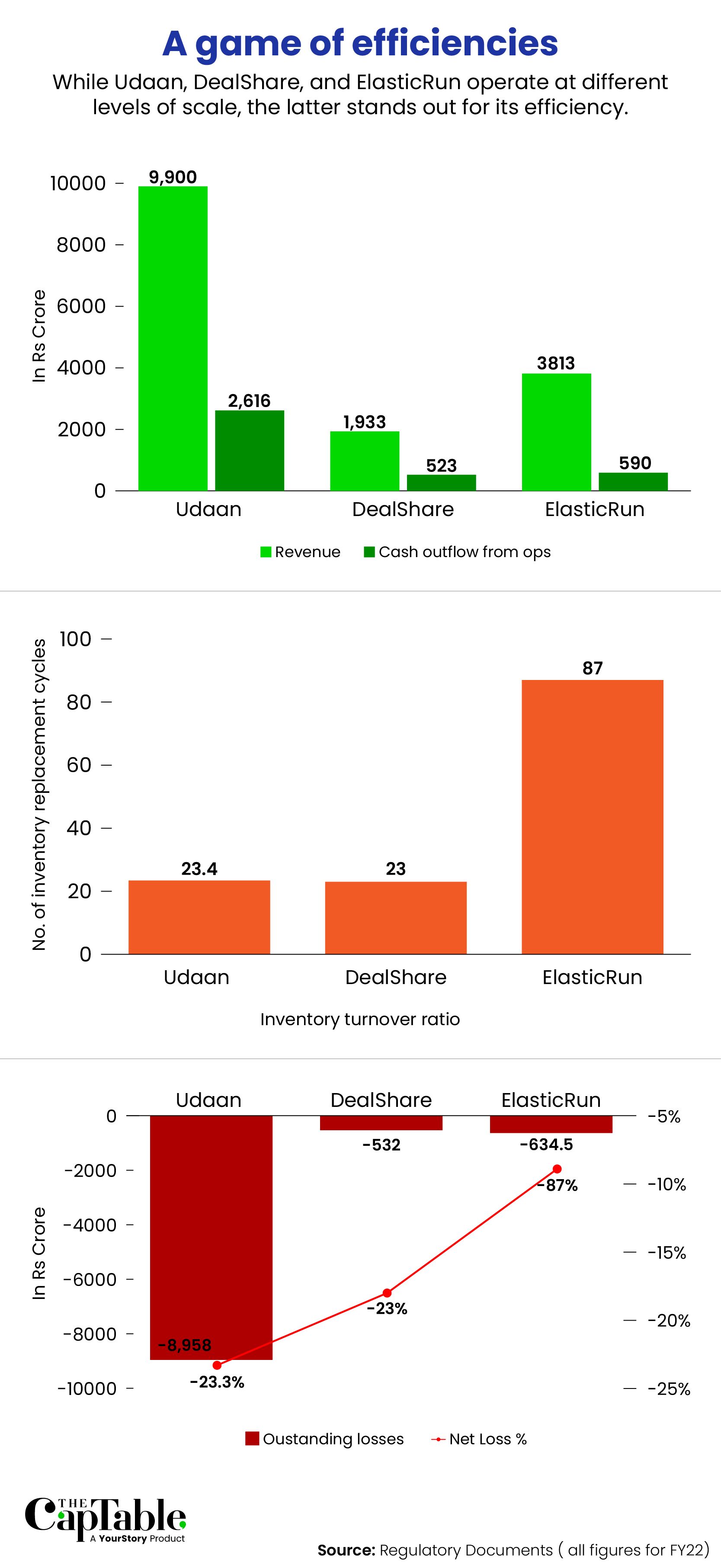

ElasticRun’s ability to navigate the choppy seas of the e-commerce B2B space is reflected in the company’s financials. Ntex Transportation, which operates ElasticRun, is still loss-making. In the year ended March 2022, it clocked a loss of Rs 373 crore on revenues of Rs 3,813 crore.

Despite this, ElasticRun is a lot closer to profitability than its peers. Its net loss percentage—loss as a percentage of total costs—for the year ended March 2022 stood at 8.9%. In contrast, the same metric for DealShare stands at 18% in the same period, while Udaan’s net loss percentage stands at 23.3%, as per regulatory filings sourced by The CapTable.

Surprisingly, it has managed this while also taking the road less travelled in India’s B2B e-commerce space. Unlike many of its competitors, it is both asset-light and has maintained its cost advantage despite focusing largely on rural India. Well begun, though, is only half done. And as ElasticRun looks to enter the next phase of its growth, it must contend both with the limitations of its own model as well as other companies looking for a piece of its hinterland pie.

Sandeep Deshmukh, CEO of ElasticRun, began his career at global logistics giant DHL. This is where he met his ElasticRun co-founders Shitiz Bansal and Saurabh Nigam. Deshmukh was also among the initial group of employees at Amazon India, where he served as the India business launch leader and played a pivotal role in establishing the American e-commerce major’s last-mile delivery network.

This combination of extensive e-commerce and logistics experience has shaped ElasticRun into a unique beast. Unlike its peers, which either have fixed supply chain assets or a combination of internal and hired resources, ElasticRun doesn’t own any part of its supply chain. Instead, it calls itself a “crowdsourced logistics” platform and uses third-party logistics (3PL) partners, eliminating the need to own trucks and other delivery vehicles.

ElasticRun doesn’t own warehouses or, by extension, hold inventory either. Instead, the company uses its technology infrastructure and machine learning capabilities to predict demand in every serviceable area and assign supply partners accordingly. The goods are either sourced from a brand-assigned distributor or directly from brands’ own warehouses.

“The biggest cost is not the cost of delivery of the service, but the cost and underutilisation of the assets,” Deshmukh tells The CapTable. “We essentially eliminate that cost of underutilisation. Hence, our landed cost on a gross level comes down substantially. That's what our technology does, that's the moat we’re building” Deshmukh explains.

This approach has seen ElasticRun build a significant cost advantage over the likes of Udaan and DealShare. During the year ended March 2022, its distribution expenses amounted to only 11% of its operating revenue, as compared to around 23.6% for Udaan and 15.4% for DealShare.

“We have built our entire network on the philosophy that we will not lose money while servicing the customer,” says Deshmukh. As a result, he adds, ElasticRun also ends up being the lowest-cost provider for the customer. “That becomes our key growth engine.”

Infographics by Nihar Apte.

“In any classic B2B e-commerce engine, the buyer and seller are both fairly well aware of the product. They understand it and understand the cost structure of the offering. This is especially true in FMCG, which is a highly commoditised market. Your procurement and service delivery cost becomes your advantage,” says Stawan Kamani, founder and CEO of FactWise, a technology-driven platform that focuses on solving procurement problems.

ElasticRun’s asset-light model also offers another significant advantage—since it doesn’t hold inventory, it encounters minimal inventory losses and can deploy its working capital elsewhere. In the year ended March 2022, its inventory turnover ratio—the rate at which a business sells out and replaces its inventory—was around 87.5 as compared to 23 for DealShare and Udaan.

“Cash management and inventory management are the cornerstones for any high-volume B2B supply chain business, and operating leakages are where these companies burn most of their money. Procurement margins and discounts also add up in the longer run but high inventory turnover is key” a senior supply chain executive tells The Captable.

Consequently, while Udaan and DealShare’s net cash outflow for the year ended March 2022 stood at Rs 2,516 crore (25.4% of operation revenue) and Rs 523 crore (27%), respectively, the same figure for ElasticRun stood at Rs 590 crore. That’s just 15.5% of the company’s operating revenue. What makes all of this doubly impressive is that ElasticRun has such significant cost advantages despite serving arguably the most difficult market—rural India.

ElasticRun began life seven years ago by providing last-mile delivery services for Amazon in Maharashtra. Even back then, ElasticRun was clear that it wanted to serve the remote and underserved towns and villages.

The appeal of rural India is twofold. For one, it is home to around half of India’s 12 million kirana stores. Beyond that, explains Deshmukh, even well-established FMCG companies like Procter & Gamble or Hindustan Unilever have limited distribution channels in rural areas due to the low density of stores. This makes these areas expensive to service for the FMCG majors, leaving them dependent on traditional distributors or wholesale traders.

ElasticRun’s rivals—including JioMart, Udaan, and DealShare—were also loath to venture into rural India because their inventory-led models require significant investments in fixed supply chain assets. This approach is only feasible in high-density markets, which allow for the optimal utilisation of these assets—be it warehouses, trucks, etc.

Mohan Aggarwal, a multi-brand FMCG distributor from Hapur, a town in western Uttar Pradesh, tells The CapTable how things typically work in his neck of rural India. “We have our own transportation service but only for stores within 10-15 km from our godown or in villages along the highway,” Aggarwal says.

Kirana store owners from interior villages, Aggarwal explains, usually come to the wholesale market in town once a week to pick up their supplies. Servicing them is unfeasible with the margins he currently gets from brands since they are all in remote locations and their order values are low. This creates a massive opportunity for ElasticRun.

Infographics by Nihar Apte.

“We have a razor-sharp focus on rural markets since we know we have a solid product-market fit there. There is tremendous pull from the brand side as well as the demand side,” Deshmukh says.

To service this demand, says Deshmukh, ElasticRun built a technology platform that allowed it to aggregate transportation and logistics resources across the length and breadth of rural India on an on-demand basis. He adds that Elasticrun is the solo last-mile grocery supplier in many of the 100,000-plus villages the company currently services.

For Rajni, who runs a small kirana store in a remote village in central Maharashtra, the service is a godsend. Before she started using ElasticRun six years ago, she and her husband had to commute over 60 km to a wholesale market to procure inventory for her store. “We had to shut our shop for 3-4 days a month and get stock from different distributors. Now, we place orders with the ElasticRun agent every Thursday and receive the stock on Friday,” she says.

In addition to the convenience, Rajni says she gets better margins on ElasticRun for FMCG goods like soap, biscuits, rice, and sugar. She now only travels to the wholesale market once a month for oil, ghee, and other local products.

While ElasticRun has a stranglehold on grocery supply in rural India, though, it knows it cannot rely on sales alone to carry it to profitability.

“Wholesale grocery and FMCG distribution businesses already operate on wafer-thin margins in India—it’s barely 4-6% at the distributor level. To attract customers who are already part of the traditional distribution value chain, companies have to go above and beyond on service. This further eats into margins” says the supply chain executive quoted earlier.

As a result, most new-age B2B distribution platforms offer ancillary services either to buyers or sellers on the platform in order to strengthen their bottom lines. Udaan, for instance, generates revenue by charging its sellers a platform fee, selling them ad space on its app, and providing them with logistics and warehousing services. It also facilitates credit for shop owners. During the year ended March 2022, Udaan generated Rs 226.5 crore from providing these ancillary services to sellers and another Rs 33.7 crore from facilitating credit for buyers. Similarly, DealShare also collects marketing income from sellers on its platform but this revenue amounted to just under Rs 7 crore in the year ended March 2022.

True to its maverick nature, ElasticRun is looking to leverage its operational efficiency and data analytics resources to carve out margins on the brand side. “One way to monetize is to offer your transportation network to various companies to deliver packages in those markets,” explains Deshmukh, referring to ElasticRun’s partnerships with e-commerce platforms such as Meesho and Flipkart. Apart from the additional revenue they generate, these tie-ups further bolster the utilisation rate of ElasticRun’s resources despite operating in such dispersed geographies.

When it comes to data analytics, Deshmukh reveals that ElasticRun is sitting on a massive amount of rural consumption data and monetises this by charging brands for access to this information. “Brands spend significant resources on building this market intelligence in relatively untapped markets. Imagine an FMCG company getting real-time insights on their product mix, promotional offers, and consumer group insights without hiring on-ground executives. That's worth a lot of money” says FactWise’s Kamani.

Like Udaan, ElasticRun, too, facilitates loans for its buyers. “With the store’s consent, we share the financial data [of their transactions on ElasticRun] with the financing partners. This gives store owners one-click access to credit after online approval,” says Deshmukh. Among the five users of this service The CapTable spoke with, their credit limits ranged from Rs 7,000-15,000.

Apart from ElasticRun earning a fee from its lending partners for every loan it facilitates, the lending offering also helps the company operate with a zero-credit policy. “We have no account receivables on our books. We leverage our lending partners to provide credit so we receive the payments as soon as the goods are handed over to the kirana store owner,” Deshmukh explains. Once again, this allows the company to free up working capital.

So far, ElasticRun’s unique approach has helped it carve out a large business for itself with minimal competition. But as with any successful endeavour, sooner or later, others start to catch on.

“We’re witnessing unprecedented development of India’s rural infrastructure and transportation network. We’re working with 3PL delivery and warehousing partners to increase their presence in the central part of the country and develop distribution hubs as other players are also eyeing a piece of the pie ElasticRun currently enjoys” a senior executive at a national logistics chain tells The CapTable on condition of anonymity.

In June, Udaan also launched its “Project Vistaar”, which involves entering 5,000 villages and small towns in Uttar Pradesh.

Apart from the increased competition on its turf, there are also concerns that ElasticRun could face obstacles to its growth. Take its no-credit policy, for instance. “We offer our regular customers a four-week, interest-free credit period, and other online platforms have also begun offering comparable options. Kirana shop owners rely on this credit period as they settle their accounts monthly with their own neighbourhood customers," says Aggarwal, the distributor quoted earlier.

In a market where there are multiple options available that offer credit periods, last-mile delivery might not be a sufficient differentiator, Aggarwal explains. Besides, he says, maintaining quality control over 3PL operators as ElasticRun expands to new geographies will also prove to be a challenge.

ElasticRun’s Deshmukh, though, doesn’t seem worried. “Last year, our goal was high-scale growth, but during the second half of the year ended March 2023, we shifted our focus to our profitability projects and pushed our long-term growth plans towards the end of the year ending March 2024. This has helped us to improve our margin profile significantly,” he says.

This shift in focus could finally push it within touching distance of profitability, a significant achievement in a space where cash has traditionally been burned en masse at the altar of growth.

Edited by Ranjan Crasta

Got a tip? If you have a lead we should be chasing at The CapTable, write to us at [email protected]

Convinced that The Captable stories and insights

will give you the edge?

Convinced that The Captable stories

and insights will give you the edge?

Subscribe Now

Sign Up Now